Subscribe & stay up-to-date with ASF

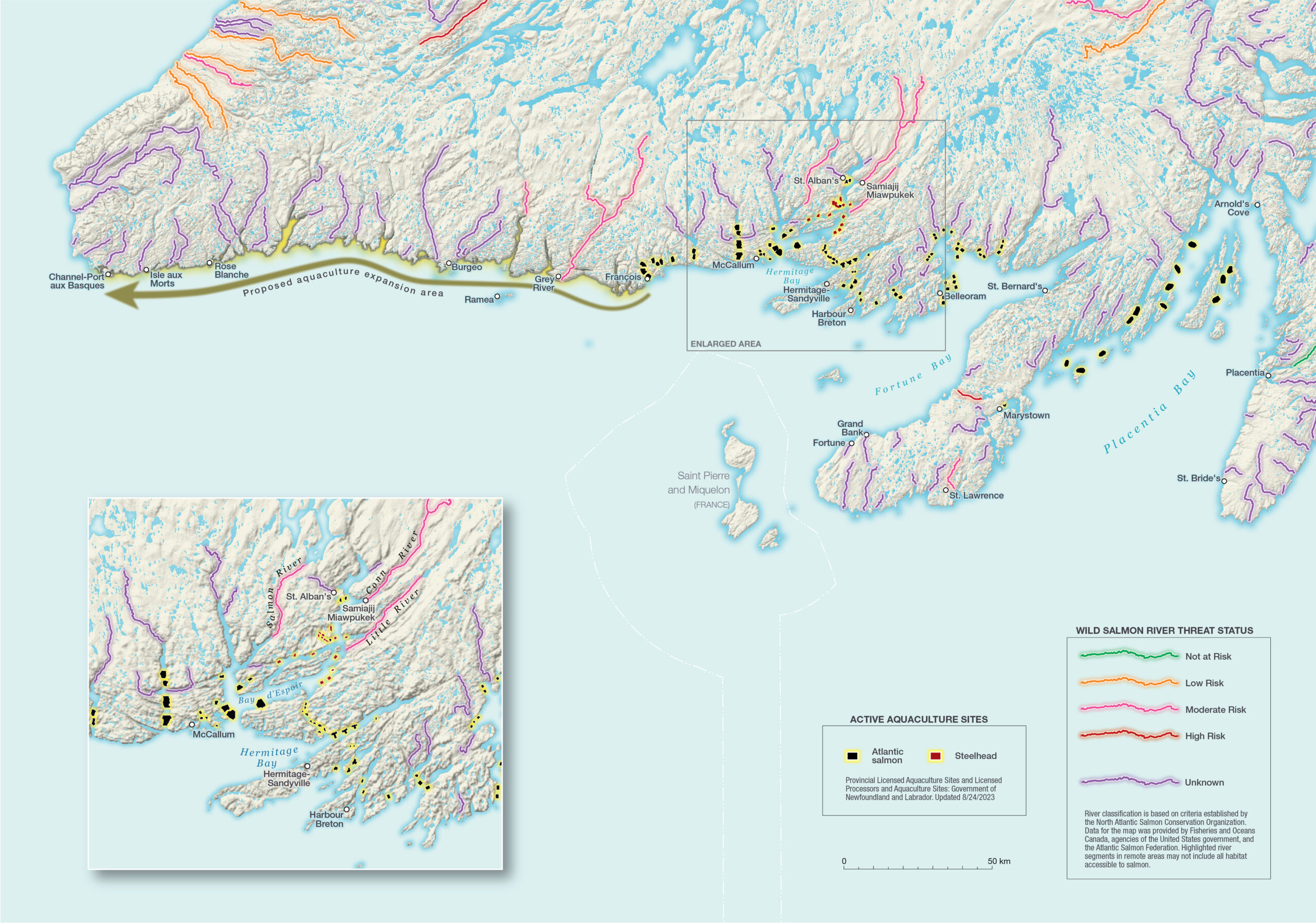

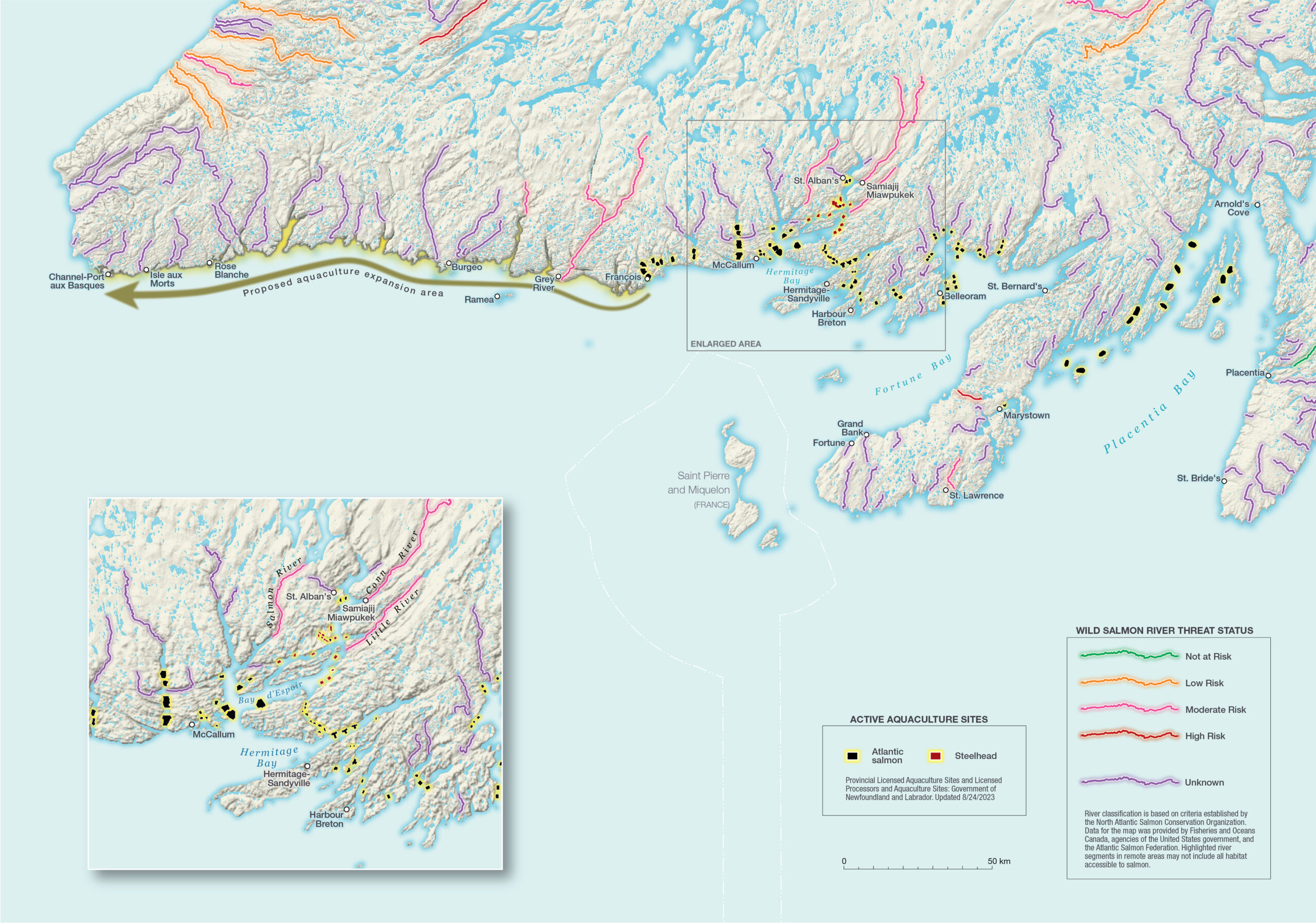

One of the largest-ever expansions of the aquaculture industry in Canada is planned for the southern coast of Newfoundland, with potentially devastating consequences for the remaining wild Atlantic salmon populations there.

In 2022 Grieg Seafood Newfoundland was announced as the successful proponent for the provincial government’s proposed expansion of aquaculture into the Bays West region on the southwest coast. Bays West consists of approximately 160 kilometres of mostly undeveloped coastline starting west of Bay de Vieux, near Grey River, and running along the coast to the La Poile Bay area towards Port-aux-Basques.

Another aquaculture company, Mowi, is also planning to dramatically expand its operations in Newfoundland by increasing capacity at its Indian Head Hatchery in Stephenville. This will lead to the addition of 2.2 million more smolt to new and existing net pens on the southern coast.

Currently aquaculture in Newfoundland is concentrated in the Bays East region east of Grey River and in Placentia Bay. Grieg’s planned expansion would extend aquaculture along almost the entire south coast. Conservation groups, including the Atlantic Salmon Federation, fear that both expansions would put salmon cages in close proximity to dozens, if not hundreds, of healthy wild salmon streams, putting those remaining healthy populations at risk.

“There are so many long-term problems that have evaded meaningful solutions, principally around escapes, disease, and sea lice, that our position is that until industry and its regulators can demonstrate that they can get these things under control, there should be no expansion,” says Neville Crabbe, ASF’s executive director of communications. “To allow expansion is in a way rewarding bad behaviour and poor performance.”

Aquaculture operations can have a variety of negative effects on nearby wild populations, says Ian Bradbury, a research scientist with Fisheries and Oceans Canada. “It’s a really complicated interaction with multiple sources of impact,” he says.

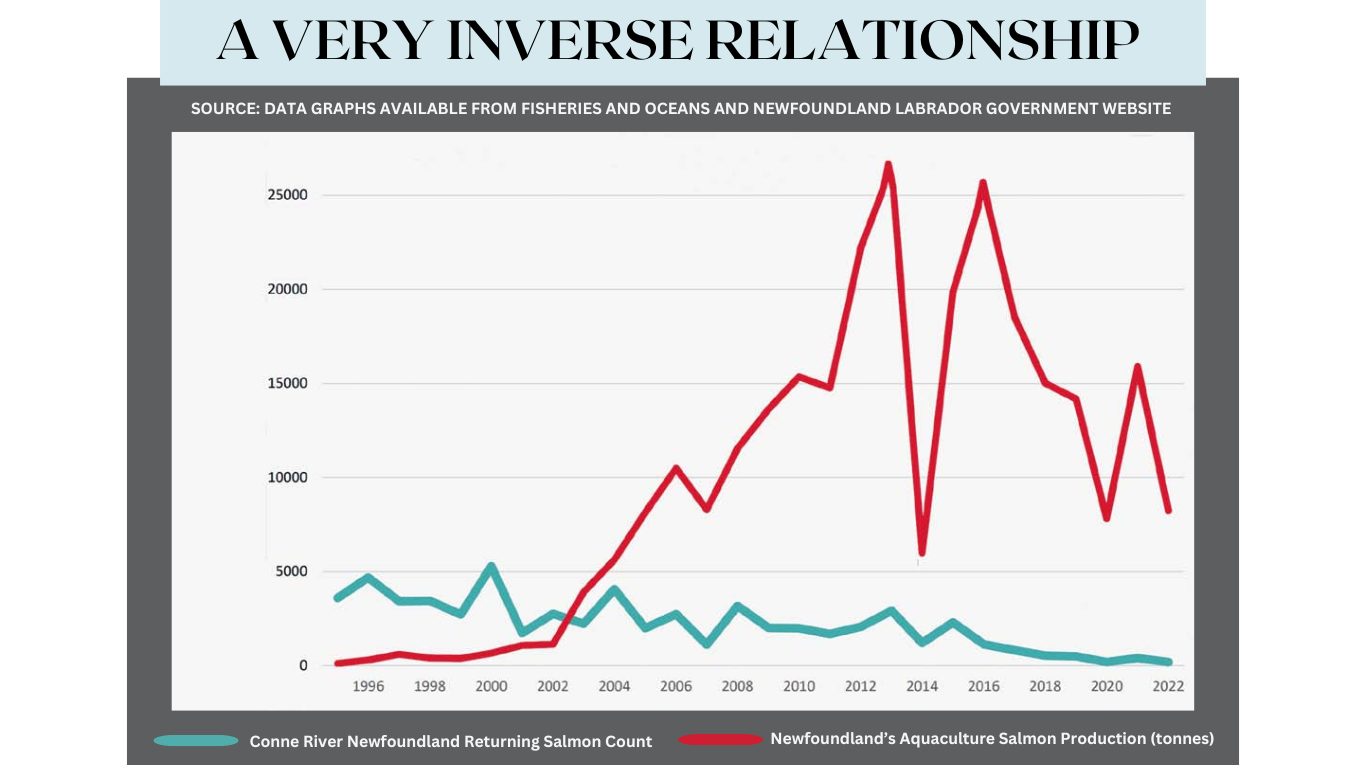

Diseases and sea lice can be transferred from net pens to passing fish, but one of the biggest concerns is the effect that escaped farmed salmon will have on wild populations.

The Conne River is “on this pretty sharp downward trajectory.”

– Nick Kelly

DFO Stock Assessment Biologist

Wild salmon have spent around 15,000 years evolving to adapt to the conditions in their native rivers – the temperature, water flow rates, pathogen communities, and more – to maximize their fitness and productivity. Farmed salmon, on the other hand, are selected for different adaptations, mainly fast growth and large size. That means that when they escape from their pens they are less able to survive in the rivers they find themselves in, while at the same time competing with their wild neighbours for food and redd sites, and potentially introducing diseases and sea lice.

And when the escapees interbreed with wild populations, their hybrid offspring are less well adapted to their native streams and unlikely to survive long. Those few hybrids that do manage to spawn continue the cycle of declining fitness, creating offspring that are more susceptible to impacts like climate change. “These farmed fish are like poodles on the loose, breeding with wolves,” says Crabbe.

In studying aquaculture escapes in Newfoundland, Bradbury has found that when the proportion of escapees in a given stream reaches around 5 to 10% of the wild population, the negative genetic effects of interbreeding start to become obvious. In small rivers like those in southern Newfoundland, where there might only be a few hundred wild fish returning each year, just a handful of escapees could have a significant impact.

And these escapes can be much larger than just a handful of fish – thousands or even tens of thousands of salmon escape from their farms around Atlantic Canada with alarming frequency. In 2013 around 20,000 farmed salmon escaped from a net pen operated by Cooke Aquaculture in Hermitage Bay, Newfoundland. Bradbury and his colleagues have been monitoring the impacts of that escape and have already found hybrid offspring in many rivers.

“The cycle is beginning,” he says. Far from bolstering declining wild populations, a sudden influx of escaped farmed salmon can have both immediate and long-term negative impacts.

While Mowi’s fish are reproductively viable, the fish that Grieg uses in Placentia Bay, and plans to use in Bays West, are a sterile European lineage, so most will not be reproductively viable. That is an important mitigation effort and significantly reduces the risk of interbreeding, says Crabbe.

Hybrids that do manage to spawn continue the cycle of declining fitness, creating off spring that are more susceptible to impacts like climate change. “These farmed fish are like poodles on the loose, breeding like wolves”

But there is a lack of trust in the aquaculture industry as a whole among many conservation groups. Over the past several years, Bradbury and his colleagues have found genetic evidence of European ancestry among escaped and hybrid wild salmon around Atlantic Canada, including at least two pure European aquaculture type salmon associated with an escape event in Newfoundland in 2015. This suggests some aquaculture companies have been stocking their pens with fish that were not approved for use in Atlantic Canada, though there is no evidence that Grieg has ever done so.

Whichever genetic stock is used in the Bays West expansion, concerns about disease and sea lice still remain, says Crabbe. And there is also the larger concern about the continued industrialization of the coastline, in one of the most species-rich and biodiverse coastal ecosystems in North America.

“There needs to be room for wild Atlantic salmon,” he says. “There is no example of ocean salmon farms and wild fish successfully mixing, one always suffers at the expense of the other.”

test