Subscribe & stay up-to-date with ASF

On a scorching summer morning, Kevin Shaw looks over an opening in the forest so massive that it defies imagination. The plot stretches three and a half kilometres and covers 300 hectares—the size of 560 football fields. The arid soil turns to dust as Shaw walks about. In one corner, just a few feet of roadway separate the harvested area from Crooked Rapids Pool on the Miramichi River.

Shaw’s family wasn’t rich. As a youngster he helped forage for blueberries and fiddleheads. Trout and salmon, along with grouse, filled the freezer. And the family counted on a deer each season. Shaw—who has lived his entire life in Juniper, N.B., in the headwaters of the Southwest Miramichi—fondly recalls a time when the river and forest were full of life: “back then, every alder had trout under it.”

Over decades, salmon population declines have led to increasingly restrictive fishery regulations, including, for anglers, mandatory live release of all Atlantic salmon starting in 2015. Shaw understands the constraints, but still laments the days when he could take a fish home. “I’d give my right arm for a feed of salmon,” he says.

Juniper is salmon country, but like most of rural New Brunswick, it’s also lumber country. In his 60 years, Shaw has had a direct view of some immense changes in the forest ecosystem. At first, he and other hunters welcomed clearcutting: deer flocked to regenerating hardwood stands. Today, however, he sees things very differently.

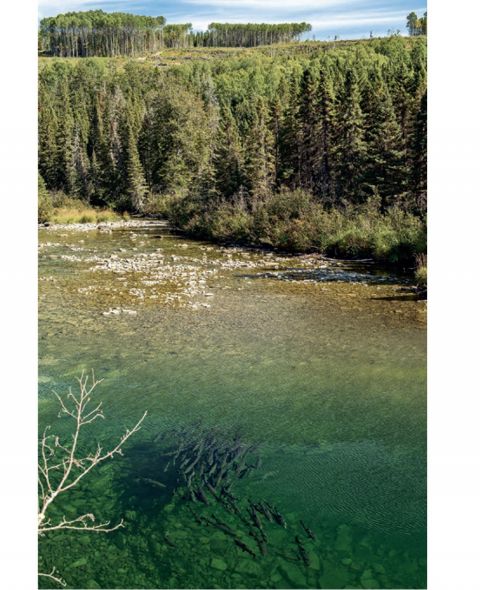

“It used to be that on a July rain you could fish for a week,” Shaw says. “Now, it’s up one day and down the next.” He sees silt accumulate in salmon pools, and slimy green algae carpet the river bottom in the heat of summer. With so few fish in the river, Shaw has all but abandoned his dream of teaching his grandchildren to fly-fish for Atlantic salmon on the Miramichi. He’s sure forestry practices are at the heart of these problems.

In New Brunswick, the forest industry has deep roots. The province’s forests are split almost evenly between public, or “Crown” Land, and private ground, sometimes called “freehold.” Four groups hold licenses to cut nearly 3.3 million hectares of New Brunswick’s public forest: A.V. Group, Fornebu Lumber, Twin Rivers Paper Company, and J.D. Irving, Limited.

A huge parcel of J.D. Irving freehold, known as the Deersdale District, drives forestry operations in the Juniper area.

The clearcut at Crooked Rapids is part of that tract.

“This is not our standard practice,” says Andrew Willett, pulling up to the cut site in early August. Willett is JDI’s director of research and engagement. He offered a tour of the company’s woodland operations for this story.

Willett explains how the trees at Crooked Rapids were blown down in 2014 during Hurricane Arthur. They snapped like twigs because they were Jack pine, planted decades ago—after clearcutting—on soil for which they were unsuitable, and therefore lacked stability. The vast clearing is a “salvage cut,” not a planned harvest. Lessons were learned says Willett.

Upriver, in the company’s Juniper tree nursery, millions of seedlings—one per pod, arranged meticulously—grow in expansive greenhouses. This facility can produce 24 million trees every year, and the pine, spruce and fir will all be planted on “appropriate” soil, Willett remarks. It’s part of a precise and technologically intensive style of forest management, which has resulted in a fourfold increase in timber on lands used this way.

Many of the seedlings from Juniper get planted inside the Deersdale District. Driving along the network of forestry roads behind company gates, Willett points to regrown conifer patches that have been managed in various ways, although all with the same goal: the production of “even aged” stands of a single species. He acknowledges that clearcuts are jarring to the eye, and that the public accepts the practice less and less. But by increasing the density of wood on some ground, Willett says JDI has reduced the footprint of clearcuts overall.

“When is a clearcut no longer a clearcut?” Willett asks rhetorically several times. It is true that trees grow back after the landscape is wiped bare. But a better question might be: “when is it a forest again?” It can take centuries for the ecological dynamics and biodiversity of an old-growth forest to reestablish.

Throughout the Maritime region, the pattern of harvest, regenerate, harvest again has eliminated all but a few stands of original forest. The landscape is carved into an industrial patchwork quilt of plantations. According to data compiled by Global Forest Watch, New Brunswick has lost 20% of its forest cover since 2000. No watercourse—and no salmon river—has been immune.

In a recent scientific study, satellite imagery showed that from 2000-2012 over 11% of the Miramichi watershed was harvested—0.92% per year. The authors of the paper call that a “high rate of depletion.” In the headwaters of the Southwest Miramichi, the average annual harvest ratio was 1.3 hectares per square kilometre, the highest in the watershed.

A wealth of scientific literature from all over the world demonstrates a strong correlation between intensive forest cutting and negative effects on freshwater: greater flows during runoff, introduction of fine sediments, up to 30-fold increases in the frequency of landslides, degradation of pool and riffle habitats, and surging summer water temperatures.

One study on Quebec’s Cascapedia River used electrofishing to measure the density of salmon parr. That data was then compared to logging intensity at several geographic scales. Very close to logging sites there was little negative correlation between harvesting and parr density. But when the scope was broadened, there was a clear adverse effect on juvenile salmon numbers.

Along with geographical scale, time is an important analytical variable. The effects of sediment, released into the water by weakened root systems, may not be statistically significant until years after logging activity. The authors of the Cascapedia study write: “Transport of fine sediments from upstream to downstream reaches over a span of decades may explain why logging effects appeared to be integrated over longer time periods at larger spatial scales.”

The authors conclude, “Large-scale disturbances arising from logging may not be detectable at smaller spatial or temporal scales.”

Other research shows increased peak stream flows after clearcutting. There is more snowpack in cut areas and root systems, which are damaged during intensive harvesting, are crucial to keeping water in the soil. Research from British Columbia shows that after clearcutting it can take 26 years for soil to regain its strength.

Intact root systems slowly disburse snowmelt and rainwater into rivers and streams. Healthy soil also clutches fine particulate, keeping stream water clear. Meanwhile, a mature forest canopy keeps the soil—and the water it bears—cold. One N.B. study shows unequivocally that groundwater in clearcuts is warmer than in forested areas.

Cool, clear rivers with stable flows— the kind of rivers that cold water fish like trout and Atlantic salmon need to thrive—require healthy, functioning forests. There is plenty of evidence that shows when the forests are damaged, so too are the rivers.

Antóin O’Sullivan, a Ph.D. student in the Canadian Rivers Institute at the University of New Brunswick, says geology also influences water flow and temperature. Some tributaries tap into water from deep below the surface, and are generally less affected by environmental factors, like warm air temperature and clearcutting.

Other streams rely more on shallow groundwater and are therefore more sensitive to landscape disturbances. O’Sullivan says, “Areas where you have shallow surficial geology with impermeable bedrock, those are the areas where you have to be careful with clearcutting. They will be more regulated by current climate.” And what about the headwaters of the Southwest Miramichi in Juniper? That’s an area that worries O’Sullivan.

O’Sullivan’s work explains why clearcutting seems to have differing effects across watercourses, but it may also have implications for forest management. J.D. Irving—which funds O’Sullivan’s research—is dedicated to protecting cold-water refugia, says Willett. He insists that when all the data is available, the company is willing to adapt its cutting practices to safeguard river habitat.

Nathan Wilbur, ASF’s New Brunswick Program Director, says it’s going to take more than minor adjustments. A fluvial geomorphologist by training, Wilbur is an expert in the functioning of river systems. He acknowledges the sector’s important economic role and the inherent complexity of forest management, but says the state of N.B.’s rivers are symptomatic of a forest industry that has simply gone too far.

“We need more than just tweaks to the current forest management practices,” says Wilbur. He calls for a forest management regime shift that would emphasize select cutting to ensure more continuous canopy coverage, as well as stronger protection for headwater forests and cold-water features.

It’s true that climate change has made hot, dry summers the new normal, which is bad news for salmon rivers. But Wilbur says that in the context of a changing climate, it’s all the more critical that we recognize the role forests play in maintaining cool water and stable flows. He describes forests and their soil as “refrigerators” that can safeguard salmon habitat from the effects of climate change. “We need resilience, and for that we need healthy forests,” Wilbur says.

“When the river’s 73 degrees at dawn, that’s a problem,” says Mike Holland, New Brunswick’s Minister of Natural Resources and Energy Development. A lifelong hunter and angler, the Minister prides himself on being accessible. Speaking over the phone while dropping his daughter off at an appointment, he describes his difficult mandate “to both cut the trees and save the trees.”

Holland agrees with Wilbur: forests and waterways are in trouble. In 2019, his government announced they would double protected areas in the province from 4.6 to 10 per cent by the end of 2020. As Holland’s boss, Premier Blaine Higgs has said, it’s an area the size of 19 Fundy National Parks and represents the largest conservation gain in New Brunswick history. But the province is also starting from the back of the pack. Currently, only P.E.I. has less protected land, and 10 per cent will fall well short of federal targets.

Still, where the new protected areas are allocated could make an important difference. In the past, it was mostly tracts unsuitable for clearcutting that were designated as protected. Holland’s staff is consulting with conservation groups, including ASF, to make sure at least some of the new areas are strategically assigned to protect sources of cold water in New Brunswick watersheds.

Holland understands the growing frustration with the state of the province’s forests. But he asks for patience, insisting that his management plan will work in the long term. “We are reclaiming areas for conservation that we might not see the results [from] today or tomorrow. New Brunswickers who aren’t even born yet are going to benefit from a healthy forest in the future.”

In Blackville, a community 150 kilometres downstream from Juniper, Brock Curtis is also thinking about the future. He looks out the window of the outfitting shop that bears his family name, at the town that was once known as the “lumber mill capitol of New Brunswick.” All of its mills have now closed.

Curtis’ family has worked, guided, and fished on the Miramichi for generations. For 40 years, he’s rented canoes and sold tackle to locals and visitors. His fly shop is known for its welcoming and warm ambience.

But like the river in August, Curtis’ business is drying up. “There aren’t enough people coming,” he says. Salmon numbers are dropping steadily. For several months of the year the water is too low even to go for a paddle on the river. “It just looks tired and worn out here,” he says. “We’ve ruined the environment.”

Curtis struggles to muster the patience that Holland is asking for. He knows the Miramichi needs a management plan that delivers real results quickly. “We’re at a crossroads,” he says. “We need to make a decision very soon.” If we don’t get the crisis in water temperature and flow under control, the damage could be irreversible. If that happens, there won’t be anything left for future generations.

Still, Curtis sees plenty of reason for hope. Younger people, he knows, are much more attuned to the environment and its needs. He believes the changes we need are entirely attainable and that perspectives are shifting.

Curtis reminisces about playing on the riverbank as a youngster, skipping rocks into the cold, clean water while his grandfather guided American anglers. He knows he can’t turn the clock back to those days. Even so, the bones of a mighty salmon river are still there. The Miramichi can be reinvigorated and saved for the future, but only if we finally recognize the forest for the trees.

Freelance writer Tom Cheney and wildlife photographer Nick Hawkins are regular contributors to the Journal and together form an Atlantic Journalism Awards winning duo.

Julie Deschênes, et al: “Context-dependent responses of juvenile Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) to forestry activities at multiple spatial scales within a river basin.” In Canadian

Journal of Fisheries and Aquaculture Science 64 (2007): 1069-1079.

Antóin M. O’Sullivan, et al: “The influence of landscape characteristics on the spatial variability of river temperatures.”

In Catena, 177 (2019) 70-83

Zeimer, R.R. “The role of vegetation in the stability of forested slopes.”

In the International Union of Forest Research Organizations Proceedings. Japan, 1981.