It’s a case of “dammed if you do, dammed if you don’t!’

NB Power operates the Milltown Generating Station, a hydro dam which spans the St. Croix River between St. Stephen and Calais, Maine.

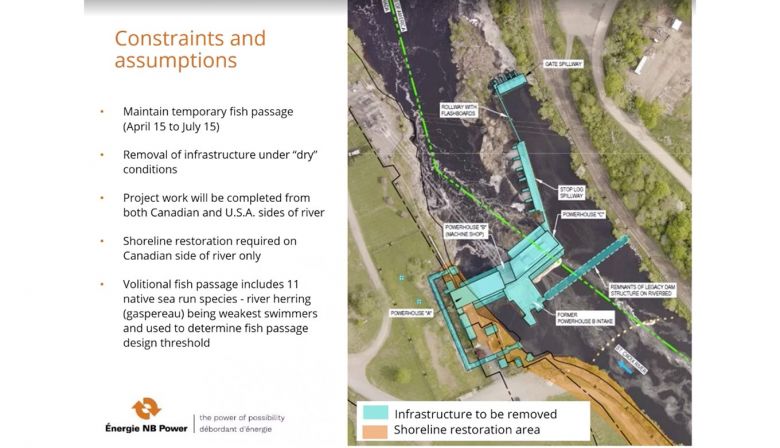

It’s slated to be decommissioned and removed by NB Power, which claims the business case for repairing the dam and its generating units is too high for too little power generation.

In the environmental impact assessment document for the dam removal registered with New Brunswick, NB Power makes it clear they considered refurbishing it, but that the cost would never be recouped. The total cost of refurbishment is likely north of $60 million, while the cost of removal is nearer $20 million. The profit from the hydro power won’t cover that multimillion-dollar gap, the utility says.

At least two other groups have made overtures to the utility to take the dam over and continue generating power, but NB Power remains committed to taking the structure out, and appears to have the support of several groups, including the Peskotomuhkati Nation, to do so. The utility is finalizing the engagement portion of the provincial environmental impact assessment, and plans to start work on decommissioning next summer, assuming all the approvals come through.

(Given the St. Croix/Skutik is a border river, it’s subject to federal, provincial and state scrutiny).

The dam is on track to be gone by spring 2023. Is this the right choice?

Dams are a tricky business because there are so many ways to think about them.

They can be tools of water flow predictability and flood prevention, support agriculture and generate power, and to some degree may enhance recreation. But there are obvious environmental impacts and forced displacement of communities – plus esthetic losses as more “wild” rivers are tamed by concrete.

My thinking on this issue is influenced by Marq de Villiers, who in his 2015 book

Back to the Well wrote a chapter entitled ‘ re dams really that bad?”

He argues that savvy activism in the late 20th century and into the 21st succeeded in depicting dams as, on balance, hugely negative. Dams, under this view, were evil tools of displacement and colonial capitalism, not to mention terrible for fish. The reliable power and water security they provide were ignored.

Indeed, several things can be true at once. Dams are bad. Dams are good.

The destruction of villages and forced relocation of local people can obviously be bad. The environmental consequences likewise aren’t pretty – habitat destroyed, fish passage hampered and rotting submerged vegetation can emit lots of carbon.

The benefits kick in, though, when reliable electricity and water are provided to people who never had it. That’s not nothing – and it muddies the picture of dams as evils imposed on the local population. Often, the local population sees substantial benefits.

Here in New Brunswick, much of that analysis applies, although we are blessed with more-than-adequate water resources, so dam reservoirs are less essential here for secure access to drinking water. St. Stephen’s water is from wells.

In Milltown’s particular case, there are additional arguments to keep it.

It’s a heritage structure, possibly the oldest hydro dam in Canada. There are also some local benefits to having a hydro facility in St. Stephen.

And, it’s not the only dam on the river: There is an argument to add or maintain dams on rivers that already have dams, and leave free-flow rivers untouched. It’s similar to the delineations made in land use decisions – allowing intensive industrial impacts in one area in exchange for setting aside a fully protected area.

Those who want the Milltown dam removed hit the predictable points: It’s a barrier to natural fish migration. Restoring free flow to 15 kilometres or so of the river’s final rush to the sea also has cultural significance for the area’s first peoples. This is the start of a river “restoration”: gaspereau are already travelling upriver in greater numbers since fish passages were improved, and perhaps with a fully open river, salmon and other migratory aquatic species will come back too.

In situations like these we may wish to have an easy choice to “follow the science” but it’s inevitably more complex. Scientific evidence can inform the decision, but it’s ultimately about what we value most, and what tradeoffs we’re willing to make.

Hydroelectricity is one of the key ways humanity can eliminate our reliance on fossil fuels, especially the coal used so widely to generate power. But while hydro is “green” – i.e. renewable and low carbon – it comes at a cost. Rivers and the ecosystems they hold are altered when a dam goes in.

Simply put, there’s no free lunch.