Further test results are pending.

It is believed the fish migrated from the nearby lake, where a decade of attempts by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans to eradicate the bass, likely introduced illegally through netting, angling and electrofishing, have failed.

The highly sensitive environmental DNA tests analyze water samples collected along the river for signs that specific fish species are living there.

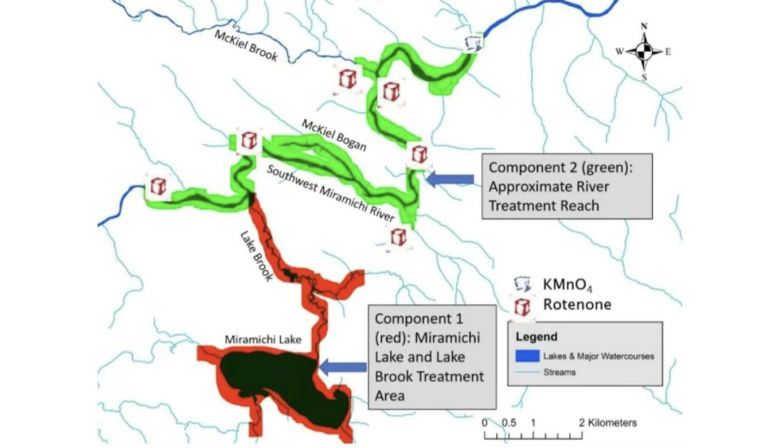

If the fish remain in that section late next summer, the rotenone plan will not have to be broadened beyond 15 kilometres, if it goes ahead.

Pesticide works quickly

Rotenone kills fish within minutes and does not distinguish between species. It has been effective in erasing invasive fish populations elsewhere in North America, although more than one application is sometimes required.

The pesticide is made from the root of certain bean plants and is poisonous to fish but biodegrades in water over a period of two weeks to 30 days or more depending on conditions.

It has been approved for use by Health Canada. A 2020 report from the US Environmental Protection Agency found no health effects linked to rotenone in human populations.

The treatment would kill almost all species of fish in the lake and the section of the river where it is applied.

In the case of Miramichi Lake, the plan is for native fish to repopulate naturally or by being transplanted from elsewhere.

In the case of the river, salmon groups will apply a product downstream at the 15 km mark to neutralize the rotenone. Some salmon would be captured and placed in a secure stream to ensure they are not killed along with the bass.

Other native species killed by the rotenone would, according to the plan, repopulate the river naturally over time.

The plan to apply the rotenone has raised alarm among a group of cottagers with camps on Miramichi Lake.

Water levels especially low

Trish Foster, who speaks for the group, said the biggest concern is that more than one treatment of the fish poison will be required to eradicate the fish in the lake.

Foster worries data on water inflow and outflow from the lake gathered this summer by members of a working group representing the salmon organizations will not reflect normal conditions because water levels are at historically low levels.

“The water in our lake is down a minimum of three feet lower than it has ever been,” said Foster. “We have people who haven’t even been able to dock their boats this summer because the water is so low.”

Foster said she wants a full environmental impact assessment rather than a simple review of the application, which could lead to an early approval.

Neville Crabbe, spokesperson for the Atlantic Salmon Federation, says the environmental impact assessment registration document will be submitted to the Department of the Environment and Local Government this Friday.

The group has concluded it is too late to implement the plan this year and is now hoping to use the rotenone in August or September, 2021.

The working group is also awaiting federal approval through the Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

“I think the reviewers will be thoroughly impressed by the level of detail in our plan, to see the magnitude of the scrutiny that this has already gone through on the federal side,” said Crabbe.

Crabbe said rejecting the rotenone application would be to reject the only option to stop the spread of smallmouth bass.

Rotenone used in Banff National Park

“That would seal the fate of the river. You could put a maximal effort into trying to remove individuals, but you would only be slowing the inevitable which would be the widespread colonization of the watershed by an invasive species.”

In the meantime, the fish killer continues to be used in Canada as a tool to control invasive species.

In August, Parks Canada used rotenone to kill fish in two lakes in Banff National Park.

Eastern brook trout were introduced to Helen Lake in the 1940s or ’50s, while yellowstone cutthroat trout were put in Katherine Lake during the same era.