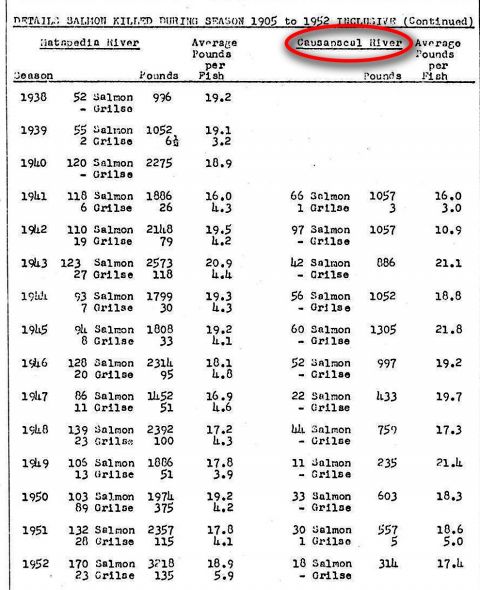

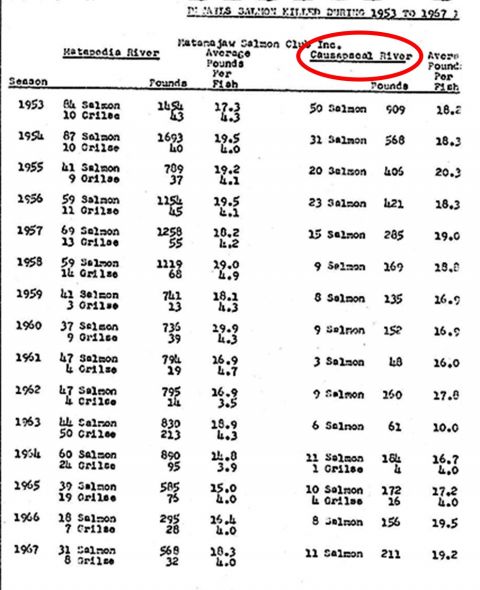

On a limited budget, it was decided that protecting wild fish, not stocking was the way forward. From a few dozen returning adults to hundreds of big salmon today, the Causapscal River alone generates hundreds of thousands of dollars in spending for the local economy every year according to a 2012 study.

Nevertheless, the Causapscal is a salmon success story, brought back from the brink of extirpation. It’s proof that involving local people in management decisions and allowing benefits to be returned to communities can have a positive effect on what’s happening under the surface.

Charles Cusson is the Atlantic Salmon Federation’s Regional Program Director for Quebec. He can be reached at ccusson@asf.ca