Subscribe & stay up-to-date with ASF

Bridging the gap between science and real world application is difficult when practicality, economy, politics, industry, social values, and funding are factored in. One of ASF’s strategic goals is to restore freshwater habitat for wild Atlantic salmon, which means addressing root causes. This includes the issue of warming rivers, and in New Brunswick, the Miramichi is ground zero. There’s an impressive set of studies on the issue, but it’s not matched by real projects that tangibly help salmon. With key partners, we are bridging the gap.

In 2009 I started a deep dive into cold water. That year I joined a team at the University of New Brunswick doing research on water temperatures in the Miramichi. Since then, I’ve learned cold water is critical to the survival of salmon and trout in North America, and have been focused on helping translate the science into conservation action.

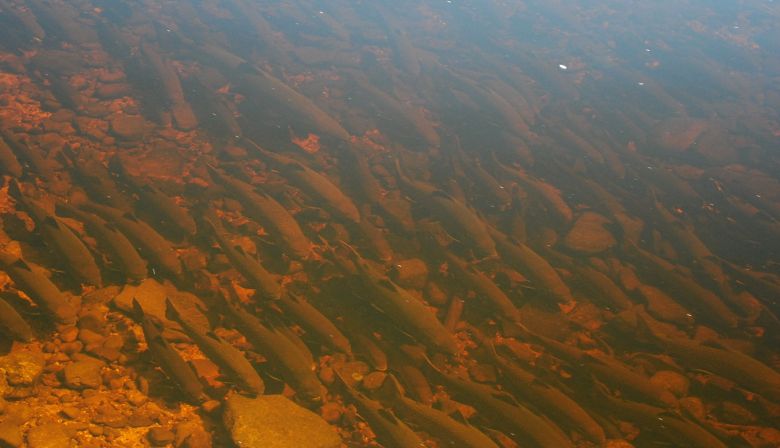

Atlantic salmon thrive in temperatures between 15 and 20 C (60-70 F), any higher and they become thermally stressed. When water temperatures exceed 25 C (77 F) it can be lethal. Salmon avoid these warm conditions and seek refuge in cold water created by brooks and springs entering rivers. These small water sources are better shaded and mostly fed by groundwater, providing a continuous supply of cold water to rivers throughout the summer.

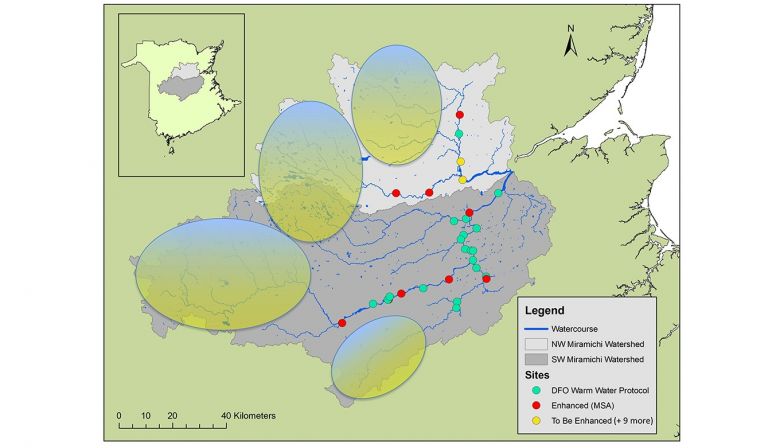

My masters project with UNB was aimed at identifying cold water refugia and characterizing how Atlantic salmon and brook trout use the habitat. This work was mostly in the Cains River, a tributary of the Southwest Miramichi. I reasoned that determining which cold water sources provide the best refuge, and understanding what makes them the best, would help enhancement projects emulate nature and create a greater number of more effective cold water sanctuaries.

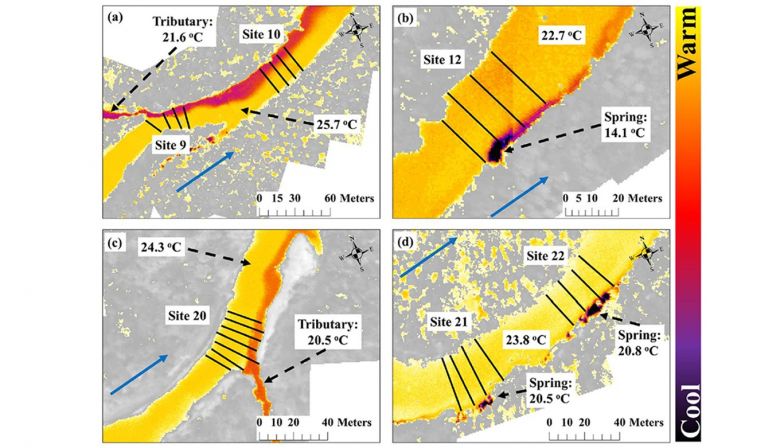

We mounted a thermal infrared camera on a helicopter and flew various sections of the Miramichi river system. In a nutshell, we found there were abundant cold water sources entering the river; however, very few of them had the physical conditions necessary to serve as refugia for fish.

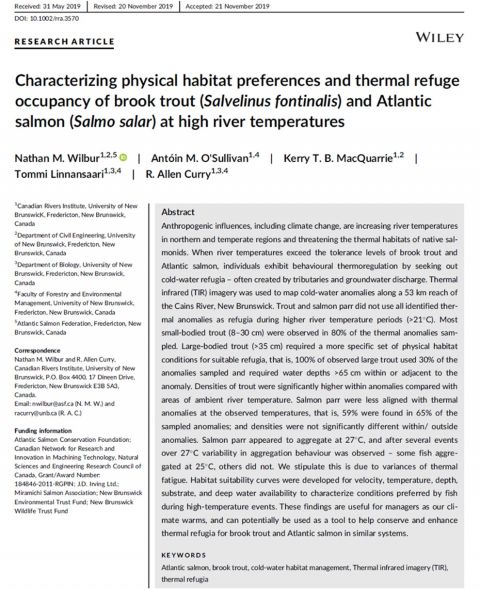

Usually, the limiting factor was depth. Particularly for large fish, the water needs to be deep enough to provide a level of protection from overhead avian predators, of which there are plenty. This means fish prefer deep and cold water, or cold water next to a deep pocket to escape into should danger appear. We recently published a peer-reviewed scientific article on this work that appeared in the journal River Research and Applications.

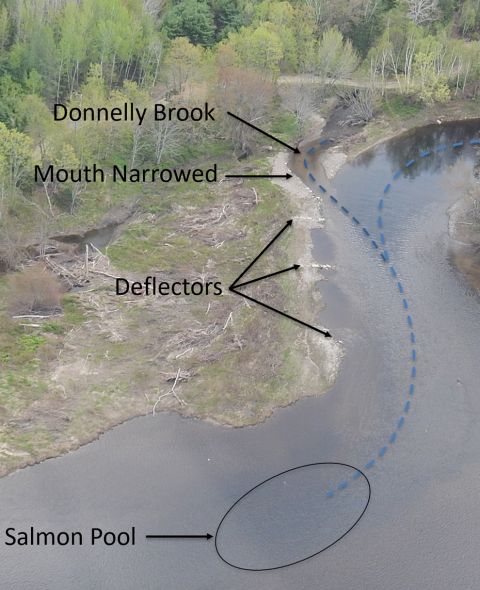

Instead, successful cold water enhancement projects work with nature by installing subtle rock structures that divert river flow into focused areas. The energy of the river then scours out pools and maintains depth where cold water flows into the river.

Using principles of fluvial geomorphology, the designs are sustainable and blend into the riverscape. Before joining ASF, I worked for an engineering firm and was fortunate to bring my knowledge to bear on some of these projects, helping bridge gap between research and application.

A new phase of this work is about to begin. A partnership has been struck between ASF, the North Shore Micmac District Council, MSA, and UNB. There will be substantial investments over the next four years to aggressively expand cold water enhancement work throughout the Miramichi watershed with more details coming soon.

While the world grapples with solutions to global warming, there are local remedies for land-use. If we expect the landscape to sufficiently regulate flows and temperatures to sustain wild Atlantic salmon, we need more healthy, intact, diverse, and mature forests.

Whether traditionally deemed sustainable, or not, the way we practice forestry throughout the province must change if we want our freshwater ecosystems to be resilient in the face of climate change.

To answer this need, the province of New Brunswick recently announced plans to increase protected areas from 4.6 to 10 per cent of the province, a contribution to national biodiversity efforts under the Canada Target 1 initiative. In real terms, this means New Brunswick will add 381,655 hectares (~950,000 acres) of protected area, about two-thirds the size of Prince Edward Island, by the end of this year.

New Brunswick’s drive to protect more of the province’s forests combined with the work of the salmon community is a major step forward. We’re optimistic that results will manifest in the short and medium term – within months and years, not decades.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/rra.3570

Wilbur, NM, O’Sullivan, AM, MacQuarrie, KTB, Linnansaari, T, Curry, RA. Characterizing physical habitat preferences and thermal refuge occupancy of brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) and Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) at high river temperatures. River Res Applic. 2020; 1– 15. https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.3570