Dealing with aquatic invasive species in Canada is the responsibility of the federal government. Although some provinces have accepted authority to permit the use of rotenone, like Nova Scotia and British Columbia, New Brunswick has not.

In 2017 our Working Group commissioned an expert report on smallmouth eradication in Miramichi Lake. The goal was to stimulate government action by demonstrating that eradication was safe and effective, but a 2018 letter from then Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) Minister Dominic LeBlanc made it clear that the federal government would, “remain solely as a regulator for such a project.”

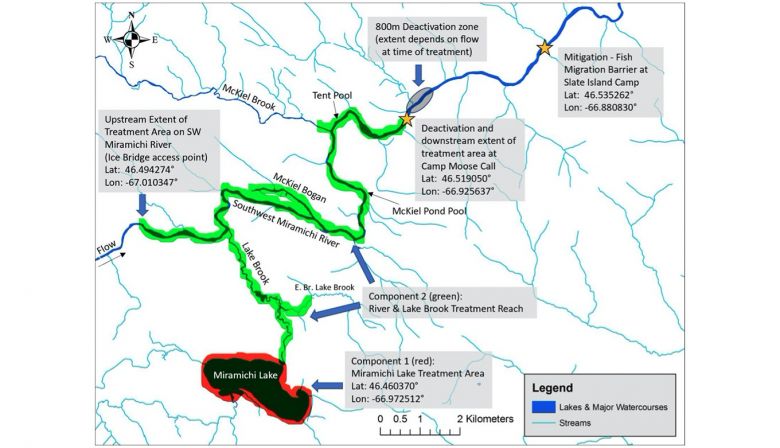

So the North Shore Micmac District Council stepped up to become the proponent in partnership with all other members of the Working Group. An application was submitted to DFO in April 2019 to treat Miramichi Lake and Lake Brook. It was amended a year later following the discovery of smallmouth in the Southwest Miramichi River.

For the project to proceed we need authorization through DFO’s Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations and permission from the New Brunswick government which is conducting an environmental impact assessment (EIA).

Seeking to satisfy DFO, we have spent the last 20 months answering multiple rounds of questions, participating in the federally-led Indigenous consultation process, and conducting extensive public and stakeholder engagement, all of which is detailed beginning on page 59 of our EIA registration document.

Through the New Brunswick EIA process we received and answered 77 questions from representatives of various provincial and federal departments and 35 questions from a group of people with cottages on Miramichi Lake. Our project also generated over 1,300 letters of support from the public.

The review has been thorough and beyond what is required in other jurisdictions. Once the process is complete, hopefully in the coming weeks, we can begin acquiring the material and equipment needed to carry out a safe and successful eradication in 2021.

Below we describe the major features of the Miramichi project, and detail our plan to stop a biological invasion of one of Canada’s great wild rivers.

SCOPING OUT THE PROBLEM