In 1968, a quiet article in the journal Science outlined what happens to spaces and resources when they are either not maintained through social structures, private ownership, or government regulation. In The Tragedy of the Commons, Garret Hardin argues that left to our own devices and self-interest, we are prone to deplete and destroy what might be described as common resources. Classic examples include CO2 emissions (the air), common pastures (the land) and, of course, fish stocks (the sea).

Canada has a dubious history of protecting fish stocks. A key example is the Atlantic cod industry, which went belly up due to poor quota policies and insatiable greed. The tragedy of the commons suggests that without limits on how much one should catch, even if we are aware, we will inevitably catch as much as we can — because everyone else will too.

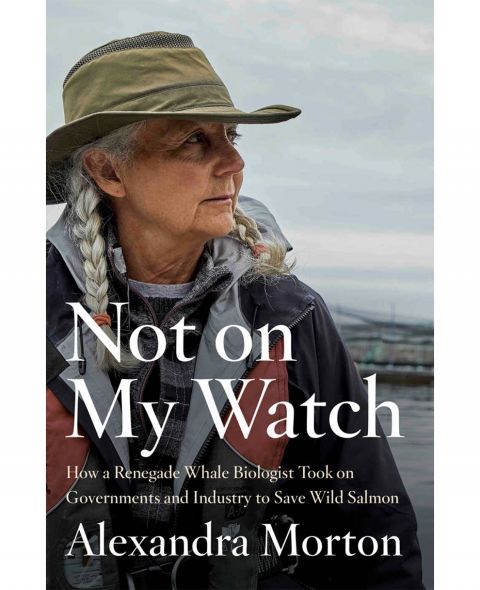

Such has been the struggle for Canadian marine biologist and activist Alexandra Morton, who for over three decades has warned Canadians and the world about the perils of industrial salmon farms off the coast of British Columbia. In Not on My Watch, Morton recounts her tireless journey to save the wild salmon stocks that have been feeding Indigenous peoples for 10,000 years.

Beginning her career researching orcas at SeaWorld in California and then off the coast in B.C., Morton characterizes her experience as a “resistance movement against extinction” and one devoted to avoiding what she calls ecocide. In her early days observing orcas in the archipelagos of coastal B.C., Morton began to notice the shifting patterns of the marine mammals; they no longer were showing up in the locations that they normally did. Digging deeper, Morton soon discovered that the industrial noise of newly and covertly implanted salmon farms were pushing the orca to other areas. What she also discovered was that these new farms were feasting off the fact that oceans were virtually unregulated — the new wild west.

Alexandra Morton, seen here in 2008 outside the B.C. Supreme Court, has more recently let First Nations communities lead lobbying, activism and legal campaigns.

As any inquisitive scientist would do, Morton began to follow the trail of diseased wild salmon, infested with sea lice, viruses, boils and sores. What she soon discovered, and what biologists in Europe had known for years, was that these new farms were breeding grounds for all sorts of pandemics and pestilence that were on track to wipe out wild salmon stocks. In the early days, she quickly realized that “Putting salmon farms in prime wild salmon habitat turned out to be as much a threat to the whales as to the salmon.”

Through initial letter campaigns and on-the-ground research her initial work focused on the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). For nearly 30 years, Morton wrote letters, pestered politicians and wrote stacks of journal articles, to no avail. Government and industry were in kahoots to reap the rewards of unbridled neoliberal capitalism — which preys on disregulation, anti-democratic levers, an ignorance of scientific fact and unlimited resources to tie up courts.

Morton could see what was happening, however, from her home on the coast. Fewer wild salmon meant less food for birds and bears, less nitrogen from fish remains leaching into the soil, and stunted forest growth — a classic response of an ecosystem, and a classic lack of understanding on government and industry’s part to understand systems thinking. For Morton, “A million salmon from the Atlantic Ocean going around in circles in a place only wild Pacific salmon know how to use properly is an abomination that nature cannot tolerate.” Things were breaking down.

https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/arts-and-life/entertainment/books/school-of-thought-574219572.html