Subscribe & stay up-to-date with ASF

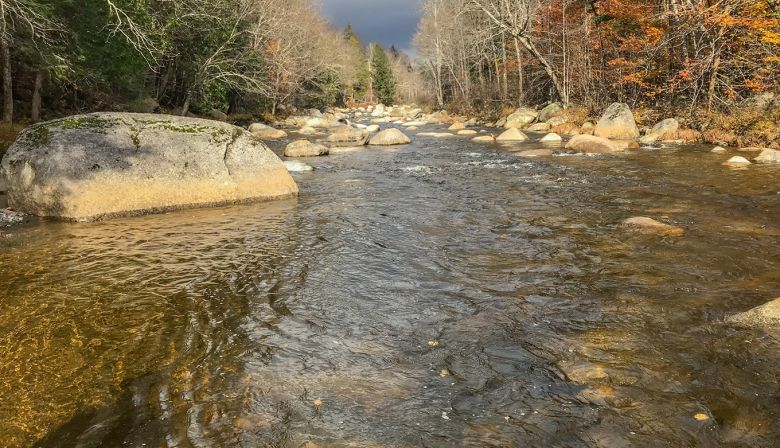

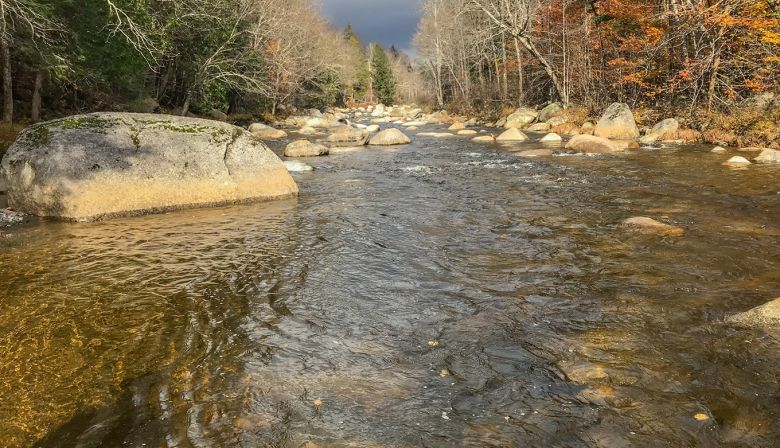

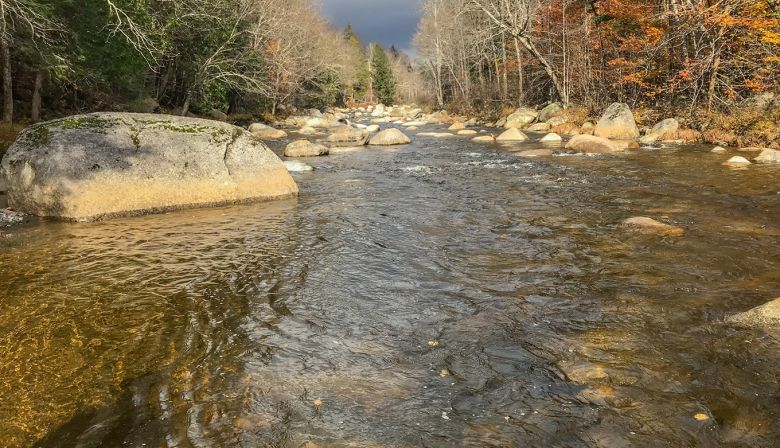

From its headwaters, the Sandy River runs fast for 70-miles (115-kilometres) to its junction with the Kennebec River near the town of Madison. It’s a mountain river with tremendous gradient, falling an average 22 feet per mile. Huge boulders dot the gravel rich riverbed, and even in the heat of summer the water is cold and gin clear. The Sandy is a prime place for Atlantic salmon, but for more than 200 years access to the sea was completely blocked by dams.

Starting in the late 1700s and stretching through to the 20th century a flurry of dam building on the Kennebec and its tributaries cut off access to historic spawning grounds for Maine’s sea-run fish. Species like alewife, American shad, striped bass, shortnose sturgeon, and Atlantic salmon almost disappeared completely from the watershed.

With no returning adults to rely on for natural reproduction, in the winter of 2002-03, state salmon biologist Paul Christman and his team modified some old refrigerators and placed them on the banks of the Sandy River. They were rigged so river water could flow through and 43,000 salmon eggs were divvied up and dropped inside.

Hatching success averaged 90% that year, but there were issues with ice build-up in the old refrigerators.

The state crew came back in the fall of 2004 with a new plan to place hatchery eggs inside incubation boxes nested in the river gravel. It was an improvement over the stream-side scheme, but still not perfect.

Eventually Christman went au natural, using water pumps and hoses to scour out artificial redds in the Sandy River, then manually depositing eggs in the gravel. So-called egg planting minimizes hatchery influence and exposes fish to the wild from the earliest life stage.

The eggs hatch when the water temperature is right. Tiny alevin with their yoke sack attached emerge from the gravel queued by Mother Nature. As fry, the young salmon disperse when conditions are optimal, all without help from human hands.

Egg planting alone can’t account for the densities of juvenile salmon found in the river today. Tests have shown that a growing number of the fry and parr are the result of natural reproduction from the 30 to 60 adults that make it back from their ocean migration each year.

These fish are true survivors, some of the most wild Atlantic salmon in the U.S. today.

Leaving the Sandy River, they navigate thousands of nautical miles of open ocean between the Gulf of Maine and the Labrador Sea. They dodge sharks and seals while constantly searching for food to feed their growing bodies.

But on the homestretch, back in freshwater, there are still thousands of tons of concrete in between them and the spawning grounds they instinctively seek out. Three of the four remaining mainstem dams on the Kennebec provide no fish passage.

Sandy River salmon are pulled out at the Lockwood Dam, placed in a tank and trucked upriver. ASF is pushing for removal of these dams to restore the Kennebec, but in the meantime, we’re focusing our efforts on one of the Sandy’s main tributaries, the long-blocked off Temple Stream.

Along with funding and engineering expertise, working with the community is an important ingredient for project success.

Near the town of Farmington, the Temple Stream flows into the Sandy River. It’s only 7-miles (11-kilometres) long, but its entire length consists of high-quality salmon habitat, currently full of fry and parr from egg-planting over the past decade. Temple Stream could be welcoming home adults trucked around the Kennebec dams, but access is completely blocked.

The Walton’s Mill Dam, a dilapidated circa 1820 structure, has never had a ladder or other fish passage. Today the structure is owned by the town of Farmington.

Faced with the prospect of an order from the federal government to construct fish passage for endangered Atlantic salmon at the cost of $750,000 U.S., several years ago ASF approached community leaders with a solution – let us pay to completely remove the structure instead.

In addition to demolition, we proposed to build a community park and erect signage telling visitors about the history of the site, all at no cost to local taxpayers.

In 2018 a yes-no question was put to voters in Farmington and residents supported the ASF-led dam removal project by a margin of two to one. Thanks to a $1,065,000 grant from NOAA Fisheries, ASF is now raising the rest of the money needed for the $3 million USD Temple Stream restoration which is set to get underway this summer.

We’re hoping to replace two problematic culverts this year, reconnecting 6 miles of cold-water tributaries to the Temple’s mainstem. We are currently finalizing engineering plans, design work, and securing all the necessary permits to remove the Walton’s Mill Dam in 2021.

Exciting things are happening for salmon in Maine. I look forward to sharing our progress with you in the coming year.