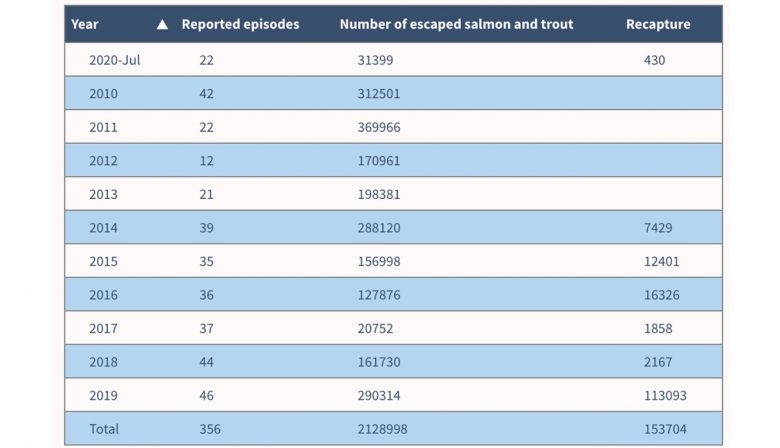

In the last decade, just over 2.1 million salmon have escaped from Norwegian farms, according to figures IntraFish gathered from Norway’s Directorate of Fisheries. However, researchers argue the number could be much higher.”

Critics of the industry, including the Institute of Marine Research (IMR), are questioning the directorate’s official figures, which are based on the number of escapes reported by fish farming companies.

Based on the agency’s 2019 risk report, the figures disclosed in the past years are only minimum estimates and the actual escape figures are potentially higher than what is reported.

Minister of Fisheries and Seafood Odd Emil Ingebrigtsen has called on fish farmers to explain recent escape incidents.

Escaped farmed salmon is a financial loss for the industry and poses a threat to wild salmon, Ingebrigtsen said. “There is no one who benefits from escape.”

Salmon industry trade body Seafood Norway declined to speculate whether actual escape figures are higher than official ones.

“The most important thing is to have documentation,” Seafood Norway Head of Communications Oyvind Andre Haram told IntraFish.

“And I have not seen any new documentation that the allegations from 2014 about five times should still apply. In that case, it would be weird.”

Salmon farming facilities are becoming more secure and the technology is constantly improving, Haram said.

“But there is no excuse for escape. We need to get better. And that is why we have a zero vision when it comes to escapes,” Haram said.

Environmentalists, river owners and the public are also concerned with the figures.

“Every escape is one too many,” wild salmon NGO Norske Lakseelver’s Pal Mugaas told IntraFish.

“Three-quarters of the Norwegian wild salmon strains are affected by escapes from fish farms. Escapes aren’t good for the survival of wild salmon strains.”

In the 1980s around one million wild salmon returned to Norwegian rivers from the open sea, Mugaas said. Since then, the number has fallen by half.

“We want the aquaculture industry to move to closed production systems, both for its own part and for wild salmon,” Mugaas said.

Ironically, Mugaas highlighted de-licing as a commonality to several escapes this year. According to the Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries, those efforts — which are viewed as a necessity both economically and to limit the parasite’s spread to wild salmon — accounted for the majority of escapes from 2014-2019.

In 2019, the proportion of fish that have escaped during work operations increased significantly, which continues through 2020.

“This is worrying because the trend shows an increase in the number of non-drug treatments, which involves work operations with a lot of activity in and around the cages,” Mugaas said.